Lattice phase equaliser

A lattice phase equaliser or lattice filter is an example of an all-pass filter. That is, the attenuation of the filter is constant at all frequencies but the relative phase between input and output varies with frequency. The lattice filter topology has the particular property of being a constant-resistance network and for this reason is often used in combination with other constant resistance filters such as bridge-T equalisers. The topology of a lattice filter, also called an X-section is identical to bridge topology. The lattice phase equaliser was invented by Otto Zobel.[1][2] using a filter topology proposed by George Campbell.[3]

Contents |

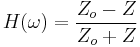

The characteristic impedance of this structure is given by;

and the transfer function is given by;

Applications

The lattice filter has an important application on lines used by broadcasters for stereo audio feeds. Phase distortion on a monophonic line does not have a serious effect on the quality of the sound unless it is very large. The same is true of the absolute phase distortion on each leg (left and right channels) of a stereo pair of lines. However, the differential phase between legs has a very dramatic effect on the stereo image. This is because the formation of the stereo image in the brain relies on the phase difference information from the two ears. A phase difference translates to a delay, which in turn can be interpreted as a direction the sound came from. Consequently, landlines used by broadcasters for stereo transmissions are equalised to very tight differential phase specifications.

Another property of the lattice filter is that it is an intrinsically balanced topology. This is useful when used with landlines which invariably use a balanced format. Many other types of filter section are intrinsically unbalanced and have to be transformed into a balanced implementation in these applications which increases the component count. This is not required in the case of lattice filters.

Design

- Parts of this article or section rely on the reader's knowledge of the complex impedance representation of capacitors and inductors and on knowledge of the frequency domain representation of signals.

The essential requirement for a lattice filter is that for it to be constant resistance, the lattice element of the filter must be the dual of the series element with respect to the characteristic impedance. That is,

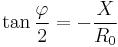

Such a network, when terminated in R0, will have an input resistance of R0 at all frequencies. If the impedance Z is purely reactive such that Z = iX then the phase shift, φ, inserted by the filter is given by,

The prototype lattice filter shown here passes low frequencies without modification but phase shifts high frequencies. That is, it is phase correction for the high end of the band. At low frequencies the phase shift is 0° but as the frequency increases the phase shift approaches 180°. It can be seen qualitatively that this is so by replacing the inductors with open circuits and the capacitors with short circuits, which is what they become at high frequency. At high frequency the lattice filter is a cross-over network and will produce 180° phase shift. A 180° phase shift is the same as an inversion in the frequency domain, but is a delay in the time domain. At an angular frequency of ω = 1 rad/s the phase shift is exactly 90° and this is the mid-point of the filter's transfer function.

Low-in-phase section

The prototype section can be scaled and transformed to the desired frequency, impedance and bandform by applying the usual prototype filter transforms. A filter which is in-phase at low frequencies (that is, one that is correcting phase at high frequencies) can be obtained from the prototype with simple scaling factors.

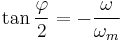

The phase response of a scaled filter is given by,

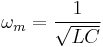

where ωm is the mid-point frequency and is given by,

High-in-phase section

A filter that is in-phase at high frequencies (that is, a filter to correct low-end phase) can be obtained by applying the high-pass transformation to the prototype filter. However, it can be seen that due to the lattice topology this is also equivalent to a crossover on the output of the corresponding low-in-phase section. This second method may not only make calculation easier but it is also a useful property where lines are being equalised on a temporary basis, for instance for outside broadcasts. It is desirable to keep the number of different types of adjustable sections to a minimum for temporary work and being able to use the same section for both high end and low end correction is a distinct advantage.

Band equalise section

A filter that corrects a limited band of frequencies (that is, a filter that is in phase everywhere except in the band being corrected) can be obtained by applying the band-stop transformation to the prototype filter. This results in resonant elements appearing in the filter's network.

An alternative, and possibly more accurate, view of this filter's response is to describe it as a phase change that varies from 0° to 360° with increasing frequency. At 360° phase shift, of course, the input and output are now back in phase with each other.

Resistance compensation

With ideal components there is no need to use resistors in the design of lattice filters. However, practical considerations of properties of real components leads to resistors being incorporated. Sections designed to equalise low audio frequencies will have larger inductors with a high number of turns. This results in significant resistance being in the inductive branches of the filter, which in turn causes attenuation at low frequencies.

In the example diagram, the resistors placed in series with the capacitors, R1, are made equal to the unwanted stray resistance present in the inductors. This ensures that the attenuation at high frequency is the same as the attenuation at low frequency and brings the filter back to a flat response. The purpose of the shunt resistors, R2, is to bring the image impedance of the filter back to the original design R0. The resulting filter is the equivalent of a box attenuator formed from the R1's and R2's connected in cascade with an ideal lattice filter as shown in the diagram.

Unbalanced topology

The lattice phase equaliser cannot be directly transformed into T-section topology without introducing active components. However, a T-section is possible if ideal transformers are introduced. Transformer action can be conveniently achieved in the low-in-phase T-section by winding both inductors on a common core. The response of this section is identical to the original lattice, however, the input is no longer constant resistance. This circuit was first used by George Washington Pierce who needed a delay line as part of the improved sonar he developed between the world wars. Pierce used a cascade of these sections to provide the required delay. The circuit can be considered a low-pass m-derived filter with m>1 which puts the transmission zero on the jω axis of the complex frequency plane.[3] Other unbalanced transformations utilising ideal transformers are possible, one such is shown on the right.[4]

See also

- All-pass filter

- Image impedance

- Zobel network

- Bartlett's bisection theorem

- Bridged T delay equaliser

References

- ^ Zobel, O J, Phase-shifting network, US patent 1 792 523, filed 12 March 1927, issued 17 Feb 1931.

- ^ Zobel, O J, Distortion Compensator, US patent 1 701 552, filed 26 June 1924, issued 12 Feb 1929.

- ^ a b Darlington, S, "A history of network synthesis and filter theory for circuits composed of resistors, inductors, and capacitors", IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems, vol 31, pp3-13, 1984.

- ^ Vizmuller, P, RF Design Guide: Systems, Circuits, and Equations, pp82-84, Artech House, 1995 ISBN 0890067546.